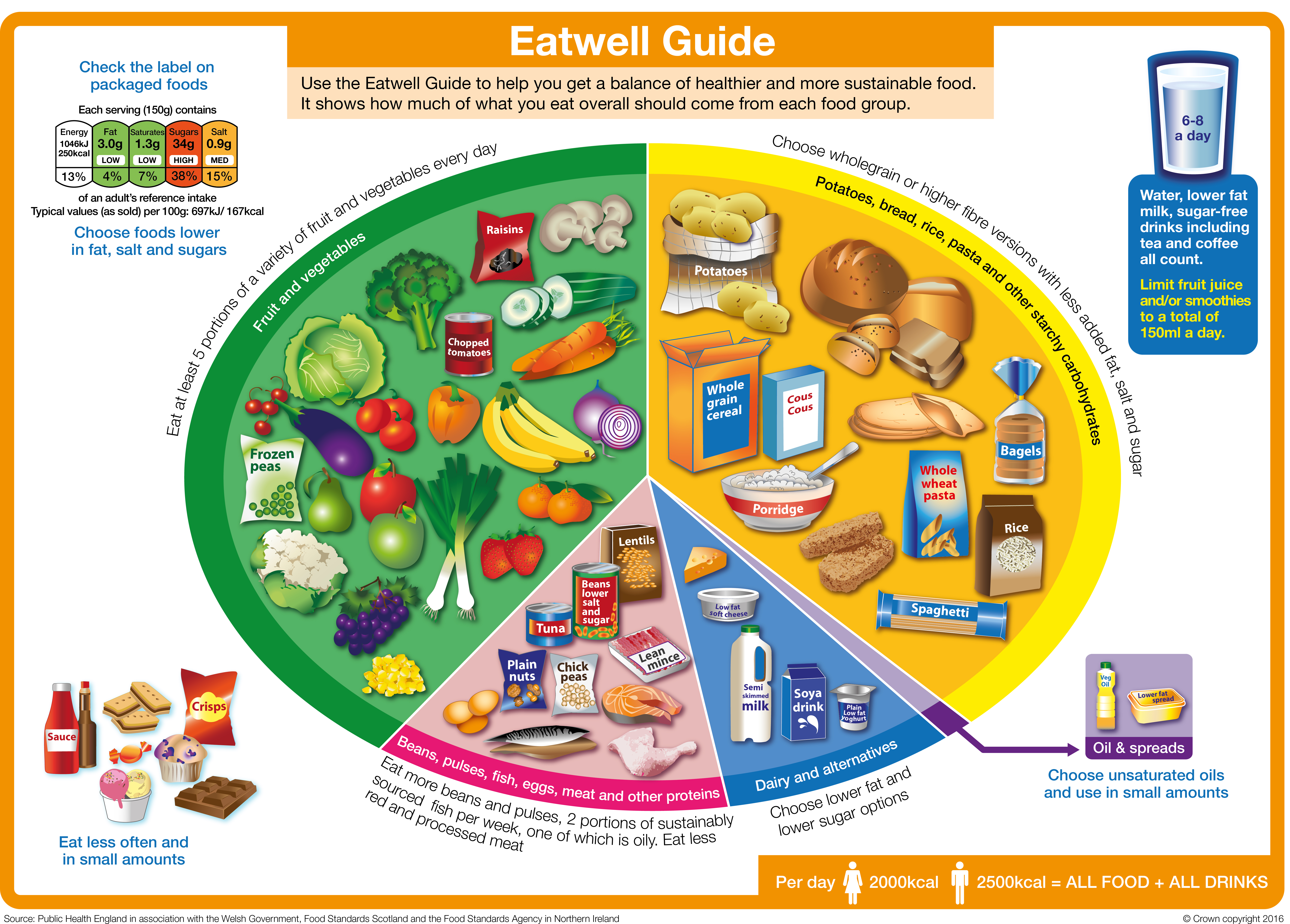

You can learn more about the Eatwell Guide on this page from the NHS.

The main food groups that feature in the Eatwell Guide, are outlined below. Each section has a useful guide to that food group.

Fruit and vegetables - eat more!

The fruit and vegetables group is the biggest in the Eatwell Guide and we are recommended to eat at least 5 A DAY. Diets high in fruit and vegetables are linked to a lower risk of diseases like heart disease, stroke and some types of cancer.

Fruit and vegetables provide a range of essential nutrients and fibre, as well as chemical compounds that occur naturally in plants that may have health benefits. Fruit and vegetables can also help you maintain a healthy weight as they are generally low in calories, so you can have plenty for relatively few calories.

Only 1 in 3 adults and 1 in 10 11-18 year olds are getting their 5 A DAY

Helena Gibson-Moore, Nutrition Scientist, British Nutrition Foundation

To get the most nutritional benefit out of your 5 A DAY it’s important to have a variety of fruits and vegetables. This is because different types and colours of fruits and vegetables contain different combinations of important nutrients such as:

- Vitamin C - important for keeping body tissues, such as skin and cartilage healthy.

- Vitamin A - important for normal vision, skin and the immune system.

- Folate - important for making red blood cells and supporting the immune system

- Potassium – important for healthy blood pressure and to support the nervous system

- Fibre – helps to maintain a healthy gut and can reduce the risk of diseases like type 2 diabetes and heart disease.

Did you know? Fresh, frozen, dried and canned fruits and vegetables all count towards our 5 A DAY.

Table 1: 5 A DAY. What counts as a portion?

|

Type

|

What counts as a portion?

|

|

Fresh, frozen or canned

|

A portion of fruit or vegetables is 80g. This is around:

- 1 medium sized piece of fruit such as a banana, apple, pear, orange or nectarine

- Half of a large grapefruit or avocado

- 1 dessert bowl of salad

- 3 heaped tablespoons of cooked vegetables like broccoli, peas or carrots.

- 2 or more small fruits such as plums, satsumas, kiwi fruit or apricots

|

|

Dried and juice

|

- A heaped tablespoon (30g) of dried fruit

- 150 ml glass of unsweetened 100% fruit or vegetable juice or smoothie counts as a maximum of 1 of your 5 A DAY.

|

|

Beans and pulses

|

- Three heaped tablespoons of beans, lentils or chickpeas counts as a maximum of 1 of your 5 A DAY.

|

You can find out more about 5 A DAY portion sizes by reading this NHS page.

5 Top Tips For Eating More Fruit & Vegetables

- Add fresh or dried fruit to breakfast cereal or porridge

- Snack on fresh fruit or vegetable sticks

- Experiment with salads – you could try using red cabbage, adding brightly coloured vegetables such as grated carrot or sliced pepper and including leftover cooked vegetables like broccoli or peas in your salads.

- Add plenty of vegetables to dishes like pasta sauces, stews or curries – frozen or canned vegetables can be a quick and easy way to do this.

- Try fruit-based puddings like fruit salad or canned/dried fruits with plain yogurt

Starchy foods - go for wholegrain and higher fibre!

Also known as ‘carbs,’ starchy foods like bread, pasta, potatoes, rice and other grains are one of the main food groups included in healthy dietary guidelines all over the world.

These foods are sometimes (incorrectly) thought of as ‘fattening’ but what’s important is the types and portion sizes we eat

Sara Stanner, Science Director, British Nutrition Foundation

Starchy foods are a key source of fibre as well as vitamins and minerals such as iron, calcium, folate and B vitamins. For a healthier diet, we should choose more wholegrains and higher fibre starchy foods, such as wholemeal breads, wholemeal pasta, wholegrain breakfast cereals or oats and potatoes with skins.

Top tip! Try swapping white versions of bread, pasta or rice for wholegrain versions, go for wholegrains cereals or oats and try other types of wholegrains such as bulgur wheat, quinoa, freekeh, barley and spelt.

Protein foods - variety is key!

In the Eatwell Guide, this food group is called ‘Beans, pulses, fish, eggs, meat and other proteins'. This group of foods are a source of protein as well as other vitamins and minerals. It is a good idea to eat a variety of different types, and to include more plant-based sources of protein, such as beans, lentils or chickpeas, as these are higher in fibre and naturally low in fat.

Nuts and seeds (plain, unsalted) are included in this food group and contain vitamins, minerals and fibre. They are also high in fat but the majority of this is ‘healthier’ fat (unsaturated) and are a nutritious option in moderation (keeping portion sizes to just a small handful).

It’s recommended that we eat at least two portions (2 x 140g cooked weight) per week of sustainably sourced fish (fresh, frozen or canned), including a portion of oily fish. Oily fish includes salmon, sardines, mackerel and trout. Fish are sources of lots of vitamins and minerals. In particular, oily fish are natural sources of vitamin D and are the richest source of a special type of fat called long chain omega-3’s, which may help to prevent heart disease.

Meat can be part of a healthy diet and can be a source of several vitamins and minerals including iron, zinc and selenium. We are advised not to eat too much red or processed meat as high consumption has been linked with a higher risk of bowel cancer. You can cut down the fat content of meat by choosing leaner cuts such as lower fat mince, cutting off visible fat and taking the skin off poultry and using less fat when cooking, such as grilling instead of frying.

Dairy foods and alternatives – go for lower sugar!

This food group includes milk, yogurt and cheese as well as plant-based alternatives to these. Dairy foods are an important source of calcium as well as protein, iodine and B vitamins. The nutritional content of dairy alternatives varies depending on what they are made from (such as soya, rice or oats) and whether they are fortified. If having dairy alternatives such as soya or oat milk, it’s best to choose those that are fortified with calcium and ideally other vitamins and minerals.

Dairy foods contain saturated fat, which we’re advised to eat less of (see below). Some studies suggest that despite their saturated fat content, dairy foods like milk, cheese and yogurt have a neutral effect on heart health. However, lower-fat versions of milk, cheese and plain yogurt are also lower in energy (calories) and so can be helpful if you are trying to manage your weight.

Fats and oils - choose unsaturated types!

There are different types of fats and oils in the diet – those that are mostly saturated such as butter, coconut oil, ghee, lard and palm oil, and those that are mostly unsaturated such as vegetable (usually rapeseed), sunflower and olive oils and spreads made from these. High intakes of saturated fat are linked to higher blood cholesterol and swapping saturated for unsaturated fats has been shown to reduce blood cholesterol and risk of heart disease. So it is a good idea to choose unsaturated fats and oils most of the time for cooking and spreading.

All fats are high in calories, even unsaturated fats, so it is important to use them in small amounts to avoid adding more calories than you need.

Foods high in fat, salt and sugar – keep portions small!

Foods high in saturated fat, salt and sugar such as crisps, sweets, biscuits, cakes, chocolate and sugary drinks are not within the main food groups of the Eatwell Guide as they are not needed as part of a healthy diet. Sometimes called ‘treat foods’ we probably all know that these are foods to eat less of. If you do include them, then it is best to have small portions – for example, those that provide about 100-150kcal such as a small chocolate biscuit bar, 4 small squares of chocolate, 2 small biscuits, a small multipack bag of crisps, a mini muffin or a small chocolate mousse.

When it comes to sugary drinks it is best to swap these for water or sugar free versions.

What is the healthy eating guidance for different dietary patterns ?

The main food groups above are the building blocks of a healthy, balanced diet but they can be put together in different ways, based on our culture, preferences and dietary requirements. There are a whole range of different types of eating but the key principles of a healthy dietary pattern run through all of these

Applying these principles to your diet will help make sure it is balanced and healthy. There are a whole range of diets out there in books, in the press and on social media, some of which claim to have specific effects on health or to help with weight loss. It is not always easy to work out whether these diets are healthy – they may be promoted by doctors or mention scientific studies.

Diets that do not follow the healthy eating principles, for example those that cut out whole food groups, are probably going to be difficult to stick with and not likely to be good for your health in the longer term.

Zoe Hill, Nutrition Scientist, British Nutrition Foundation

The Mediterranean diet

The Mediterranean diet is often thought of as one of the healthiest eating patterns and features plenty of fruit, vegetables, pulses, wholegrains, olive oil, fish and smaller amounts of meat, dairy, eggs and sugary foods. A Mediterranean diet contains a higher proportion of fat than other healthy eating patterns, but most of this is unsaturated fats from olive oil, nuts and seeds and oily fish. This style of eating may reduce the risk of heart disease and have other potential health benefits. If this way of eating works for you then that’s great! However, it is not the only way to eat healthily, and may not work for everyone.

Vegetarian and vegan diets

Vegetarian and vegan diets have had a lot of interest and some research suggests that these diets may reduce the risk of heart disease. A healthy, balanced vegetarian or vegan diet will typically provide plenty of vegetables, pulses and wholegrains and so be rich in fibre and low in saturated fat.

Plant-based diets

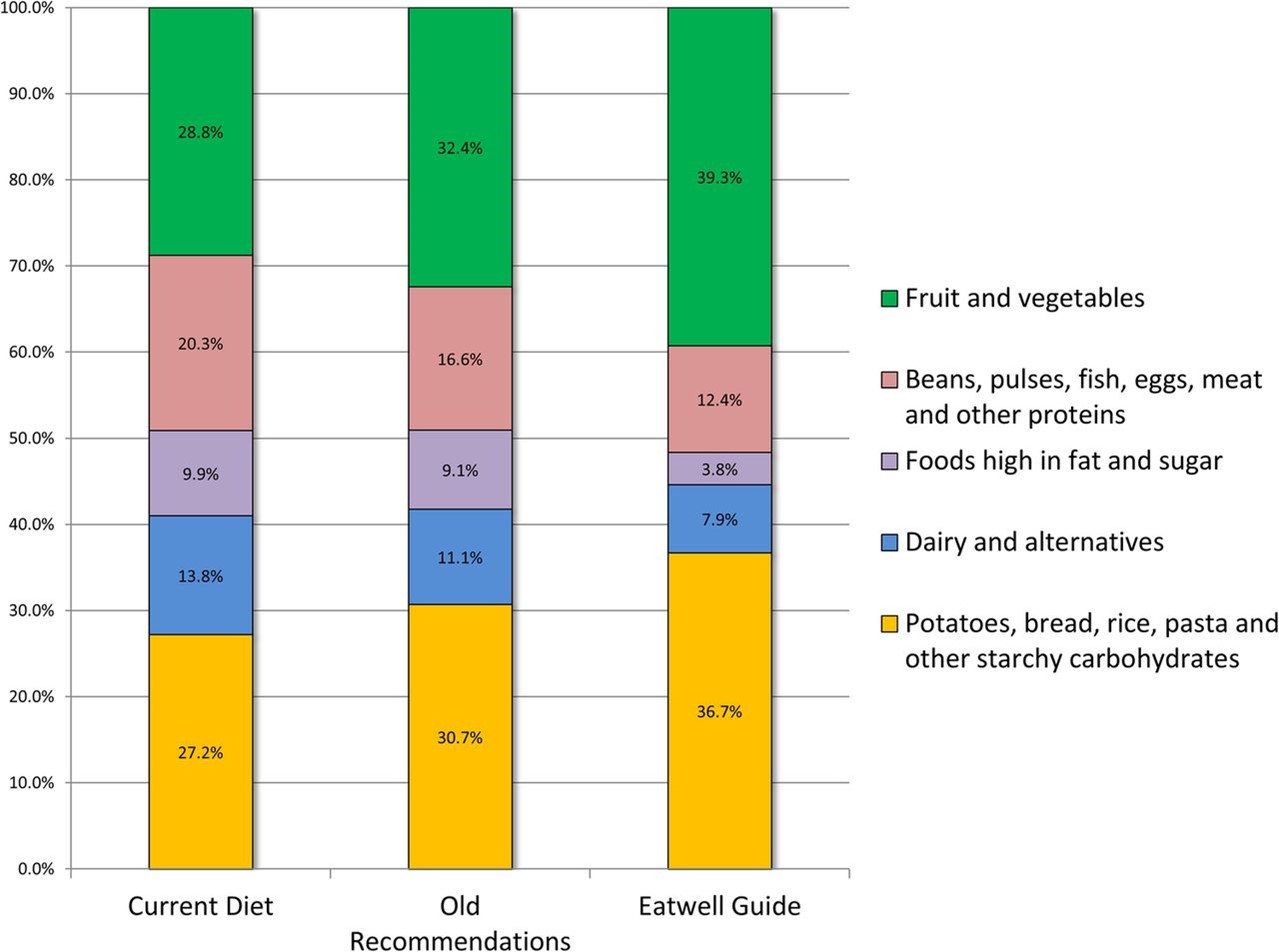

The term ‘plant-based diet’ is increasingly popular but there is some confusion about what it means. Some people think this refers to a vegetarian or vegan diet, but many authoritative bodies agree that plant-based eating means proportionately choosing more of your foods from plant sources and so is a diet mainly made up of plant foods, but may still include some meat, fish, eggs and dairy foods. Most healthy eating guidelines, including the Eatwell Guide recommend a mainly plant-based diet. The two biggest food groups; fruit and vegetables and starchy foods, are both plant-based and we are also encouraged to eat more beans and pulses and to use plant-based oils and spreads. So you can make your diet more ‘plant-based’ by including a wider variety of fruits and vegetables, including wholegrains as well as choosing more plant-based sources of protein.